Data Structures

- Vectors

- Maps

Group of data - Collections

So far, we’ve dealt with discrete pieces of data: one number, one string, one value. When programming, it is more often the case that you want to work with groups of data.

Clojure has great facilities for working with these groups, or collections, of data. Not only does it provide four different types of collections, but it also provides a uniform way to use all of these collections together.

Vectors

Sequential collection

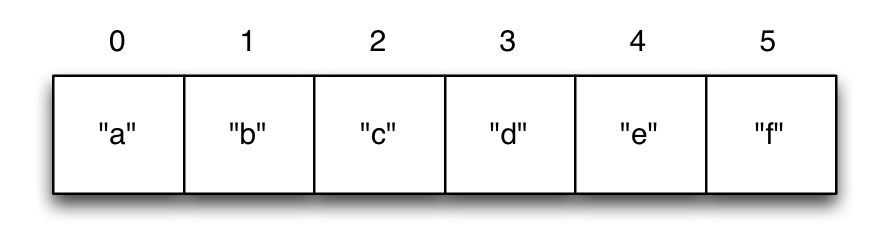

A vector is a sequential collection of values. A vector may be empty. A vector may contain values of different types. Each value in a vector is numbered starting at 0, that number is called its index. The index is used to refer to each value when looking them up.

Compartment-like structure

To imagine a vector, imagine a box split into some number of equally-sized compartments. Each of those compartments has a number. You can put a piece of data inside each compartment and always know where to find it, as it has a number.

Note that the numbers start with 0. That may seem strange, but we often count from zero when programming.

Syntax

Vectors are written using square brackets with any number of pieces of data inside them, separated by spaces. Here are some examples of vectors:

[1 2 3 4 5]

["Grace Hopper" 1906 1992]

[]

Creation

Instead of writing a vector with square brackets, you can also use the vector function to create a vector. All arguments are collected and placed inside a new vector.

conjtakes a vector and some other values, and returns a new vector with the extra value added.conjis short for conjoin, which means to join or combine. This is what we’re doing: we’re joining the extra value to the vector.conjcan be used with any kind of collection. Right now the only kind of collection we’ve encountered is a vector.

(vector 5 10 15)

;=> [5 10 15]

(conj [5 10] 15)

;=> [5 10 15]

Extraction

Now, take a look at these four functions.

countgives us a count of the number of items in a vector.nthgives us the nth item in the vector. Note that we start counting at 0, so in the example, callingnthwith the number 1 gives us what we’d call the second element when we aren’t programming.firstreturns the first item in the collection.restreturns all except the first item. Try not to think about that andnthat the same time, as they can be confusing.

(count [5 10 15])

;=> 3

(nth [5 10 15] 1)

;=> 10

(first [5 10 15])

;=> 5

(rest [5 10 15])

;=> (10 15)

EXERCISE: Make a vector

- Go to your REPL

- Make a vector of the high temperatures for the next 7 days in the town where you live.

- Then use the

nthfunction to get the high temperature for next Tuesday.

Maps

key value pairs

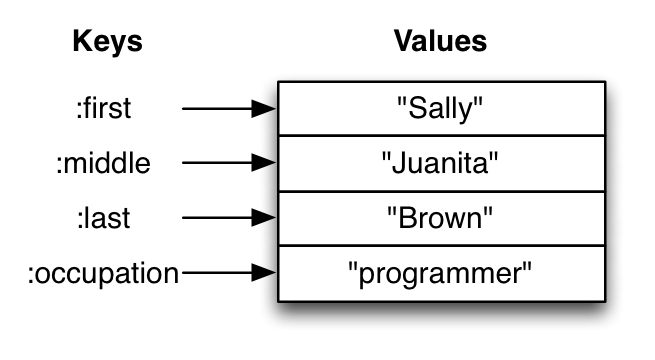

Maps hold a set of keys and values associated with them. You can think of it like a dictionary: you look up things using a word (a keyword) and see the definition (its value). If you’ve programmed in another language, you might have seen something like maps–maybe called dictionaries, hashes, or associative arrays.

Syntax

We write maps by enclosing alternating keys and values in curly braces, like so.

Maps are useful because they can hold data in a way we normally think about it. Take our made up example, Sally Brown. A map can hold her first name and last name, her address, her favorite food, or anything else. It’s a simple way to collect that data and make it easy to look up. The last example is an empty map. It is a map that is ready to hold some things, but doesn’t have anything in it yet.

{:first "Sally" :last "Brown"}

{:a 1 :b "two"}

{}

Creation

assocanddissocare paired functions: they associate and disassociate items from a map. See how we add the last name “Brown” to the map withassoc, and then we remove it withdissoc.mergemerges two maps together to make a new map.

(assoc {:first "Sally"} :last "Brown")

;=> {:first "Sally", :last "Brown"}

(dissoc {:first "Sally" :last "Brown"} :last)

;=> {:first "Sally"}

(merge {:first "Sally"} {:last "Brown"})

;=> {:first "Sally", :last "Brown"}

Extraction 1

count, every collection has this function. Why do you think the answer is two?countis returning the number of associations.

Since map is a key-value pair, the key is used to get a value from a map. One of the ways often used in Clojure is the examples below. We can use a keyword like using a function in order to look up values in a map. In the last example, we supplied the key

:MISS. This works when the key we asked for is not in the map.

(count {:first "Sally" :last "Brown"})

;=> 2

(get {:first "Sally" :last "Brown"} :first)

;=> "Sally"

(get {:first "Sally"} :last)

;=> nil

(get {:first "Sally"} :last :MISS)

;=> :MISS

Extraction 2

Then we have

keysandvals, which are pretty simple: they return the keys and values in the map. The order is not guaranteed, so we could have gotten(:first :last)or(:last :first).

(keys {:first "Sally" :last "Brown"})

;=> (:first :last)

(vals {:first "Sally" :last "Brown"})

;=> ("Sally" "Brown")

Update

After the creation, we want to save a new value associated to the key. The

assocfunction can be used by assigning a new value to the existing key. Also, there’s handy functionupdate. The function takes map and a key with a function. The value of specified key will be the first argument of the given function. Theupdate-infunction works likeupdate, but takes a vector of keys to update at a path to a nested map.

(def hello {:count 1 :words "hello"})

(update hello :count inc)

;=> {:count 2, :words "hello"}

(update hello :words str ", world")

;=> {:count 1, :words "hello, world"}

(def mine {:pet {:age 5 :name "able"}})

(update-in mine [:pet :age] - 3)

;=> {:pet {:age 2, :name "able"}}

Collections of Collections

Simple values such as numbers, keywords, and strings are not the only types of things you can put into collections. You can also put other collections into collections, so you can have a vector of maps, or a list of vectors, or whatever combination fits your data.

Vector of Maps

(def characters

[{:name "Snoopy"

:species "dog"}

{:name "Woodstock"

:species "bird"}

{:name "Charlie Brown"

:species "human"}])

(:name (first characters))

;;=> "Snoopy"

(map :name characters)

;;=> ("Snoopy" "Woodstock" "Charlie Brown")

EXERCISE: Modeling Yourself

- Using the Clojure REPL

- (Option) You may create a new file and write code in the file. To

evaluate, set the cursor next to the code you want and hit ctrl/cmd + shift + r, or press the

Reload Selectionbutton

- (Option) You may create a new file and write code in the file. To

evaluate, set the cursor next to the code you want and hit ctrl/cmd + shift + r, or press the

- Make a map representing yourself

- Make sure it contains your first name and last name

- Then, add your hometown to the map using assoc or merge.

EXERCISE [BONUS]: Modeling your classmates

- First, take the map you made about yourself in previous exercise.

- Then, create a vector of maps containing the first name, last name and hometown of two or three other classmates around you.

- Lastly, add your map to their information using conj.

Return to the first slide, or go to the curriculum outline.